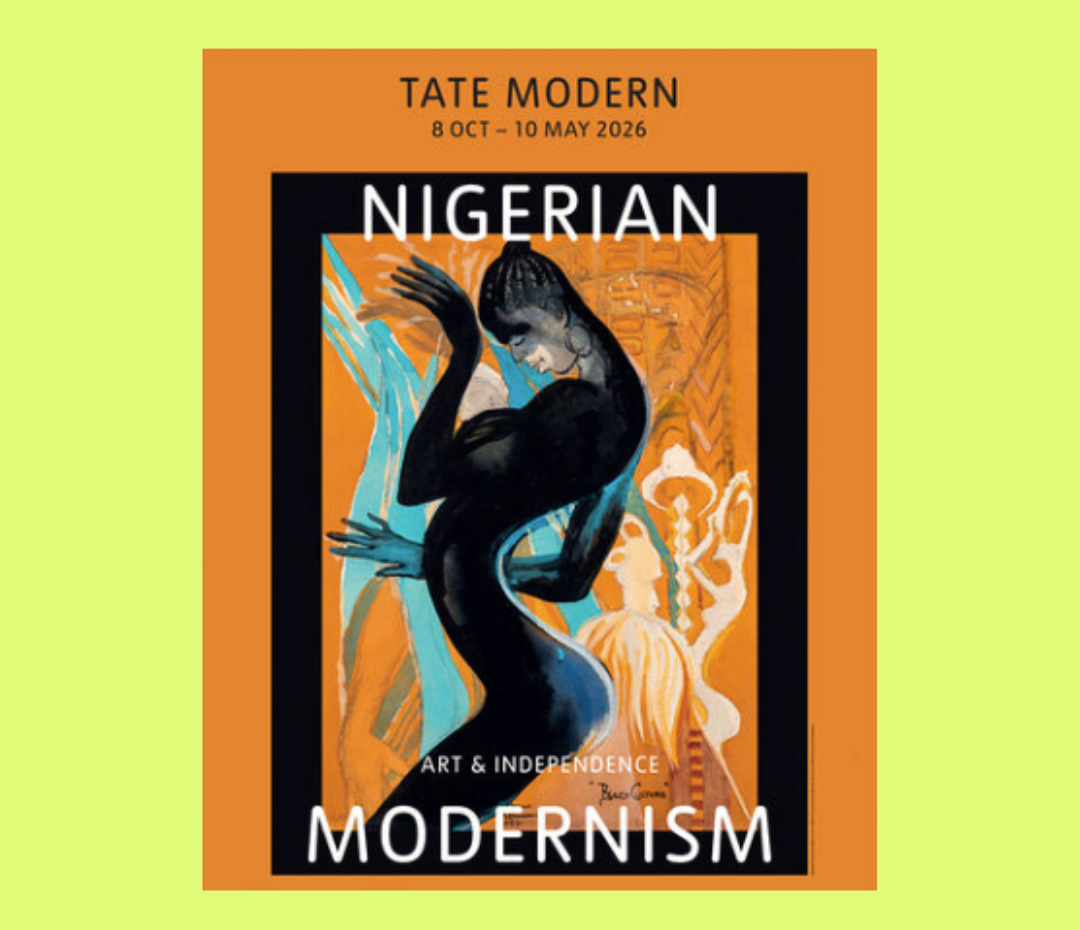

Photo Credit: GGD x Ben Enwonwu, Black Culture (1986), Tate Modern

More than 250 works unfold across 9 rooms at Tate Modern, and yet what hits first isn’t Nigerian Modernism‘s scale, but its density. Textured, saturated, vibrant layers are everywhere in the exhibit. Fabrics look like paintings. Paintings are enveloped in music or poetry. Doors are sculpted with royalty and scenes of daily life. Nothing is quiet. Nothing is random. It’s an ordered chaos.

Despite the stylistic range, there’s an inescapable sense of hope threaded through the exhibition; all tied to longing, ambition, belief. Maybe that reads louder if you’re Black, African. As someone who often walks through museums acutely aware of being the minority, this did feel different. There was excitement. Awe. And also a strange realization of how much you miss or forget when histories aren’t centered. When recollections or memories are never captured.

You can’t finish this exhibition in one visit. It isn’t tucked into a “free” section either. People paid to be here, and the rooms were crowded. Both the actual art pieces and the exhibition’s overall presentation made a statement. For Black modern African art, curated from a specific region (not jumbled together from different places/times into a catchall “Africa”), to take up an entire floor at one of the world’s most prestigious museums is rare, and revolutionary in itself.

Here’s a room-by-room breakdown, highlighting a key artwork from each space.

Room 1 | Figuring Modernity

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; Yoruba Acrobatic Dance, 1963 by Akinola Lasekan, oil paint on canvas, Collection of the Hampton University Museum, Hampton, VA; Gift of the Harmon Foundation

The opening room hums with anticipation. Similarly, Lasekan’s painting captures a dancer flipping midair, surrounded by a curious but excited crowd. All the items in the room work to give visitors a sense of how Nigerian artists began to define modernity on their own terms, even with the fog of colonialism hanging overhead.

Room 2|Ghosts of Tradition

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; Untitled (Seven Wooden Sculptures), 1961 by Ben Enwonwu, ebony, Access Holdings Art Collection

These wooden figures stand in a row at the center of the room, reading, yet resembling carved angels in varied postures. “Ghosts of Tradition,” is dedicated entirely to Ben Enwonwu, often cited as the first African modernist to gain international recognition. Enwonwu combined his Igbo artistic training with experiences gained at London’s Slade School of Fine Art, and both his sculptures and paintings are represented here. A giant image of him working on a bronze sculpture of Queen Elizabeth II looms above the winged Seven Wooden Sculptures, creating a quiet discomfort that lingers throughout the space.

Room 3 | Ladi Kwali: Of Soil and Stone

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; Leaflet advertising Ladi Kwali 1972 tour and featured pottery, Craft Study Center, University for the Creative Arts

Painted a peachy orange, the walls of “Of Soil and Stone” make Ladi Kwali’s pottery glow. She proved ceramics could be both modern art and cultural record. The room shows how she transformed traditional pottery techniques into a modern language. The displayed leaflet (above), shown alongside photos of her on tour, is not technically artwork, but it underscores how open and accessible she was with her process. Like her pottery, Kwali’s creative methods, labor, and ancestral knowledge were always on display, for better or worse.

Room 4 | New Art, New Nation: The Zaria Art Society

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; The Last Supper, 1981 by Bruce Onobrakpeya, sculpture made in resin, wood, metal, and paint. Surrounded by The Fourteen Stations of The Cross, 1969, linocut, Purchased by the Africa Acquisitions Committee, 2019

This room reflects a generation determined to define a post-independence visual language. Rejecting strict European academic standards, members of the Zaria Art Society embraced “Natural Synthesis,” blending Western training with Indigenous forms. Bruce Onobrakpeya’s The Last Supper captures that ambition using his signature plastocast technique. Surrounded by his prints of The Fourteen Stations of the Cross, the scenes relocate the biblical narrative to southwestern Nigeria through Yoruba architecture, Adire textiles, and colonial uniforms. It is both spiritual and political, asserting that modern Nigerian art could reinterpret religious stories on its own terms rather than Europe’s.

Room 5 | Eko

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; Untitled images of “Hairstyles” series, 1971-75 by JD Okhai Ojeikere, gelatin silver print on paper, Purchased by the Acquisitions Fund for African Art, 2013

“Eko” is the precolonial name for Lagos, and this room treats the city as its own visual language. Ojeikere’s Untitled “Hairstyles” photographs make that point instantly. A total of eight are featured in “Eko.” He took nearly 1,000 images celebrating Nigerian hair design, and the eight untitled prints featured turn everyday style and innovation into sculpture, pattern, and pride.

Room 6 | Forest of a Thousand Spirits: New Sacred Art Movement

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; Mythos Odudùwà Schöpfungsgeschichte (Oduduwa Creation Myth), 1963 by Susanne Wenger, cassava starch batik, Susanne Wenger Foundation

This room draws from the 400-year-old Osun-Osogbo Sacred Groves, a UNESCO World Heritage site dedicated to Osun, the Yoruba river goddess of prosperity and fertility. It highlights how artists within the New Sacred Art Movement revived and reimagined spiritual traditions through contemporary form. In Mythos Odudùwà Schöpfungsgeschichte (Oduduwa Creation Myth), Austrian artist turned Yoruba priestess Susanne Wenger used Adire, a traditional indigo-dyed cloth, drawing her figures with cassava starch to visualize sacred origin stories and merge ritual, craft, and modern art into a single devotional language. Here, art functions as spiritual practice.

Room 7 | Festival of the Gods of the Oshogbo School

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; The Garden of Eden, 1965 by Asiru Olatunde, repoussé aluminium panel, Tiana & Vikram Chellaram

The exhibit’s seventh room reflects the experimental energy that grew out of the Oshogbo workshops in the 1960s, where folklore and bold visual language met post-independence ambition. Centered around the Mbari Mbayo Club, the movement opened artistic training to local performers and craftspeople, helping establish Osogbo as a cultural force grounded in Yoruba belief and storytelling. In The Garden of Eden (1965), Asiru Olatunde reimagines a biblical narrative through repoussé aluminium, merging Christian imagery with Yoruba cosmology and decorative tradition. The result feels both devotional and distinctly local, capturing the Oshogbo School’s commitment to spiritual hybridity and accessible creativity.

Room 8 | Nsukka School

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; Our Journey, 1993 by Obiora Udechukwu, ink and acrylic paint on stretched canvas, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire

The Nsukka School room highlights artists connected to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, who fused contemporary painting with visual traditions, especially uli design work. As head of the fine arts department, Igbo artist Obiora Udechukwu encouraged students to use their local environments and reclaim their heritages. The room reflects how personal memory and national history became inseparable in late 20th-century Nigerian art. In Our Journey (1993), Udechukwu paints a bold yellow spiral symbolizing the sacred python, a divine guide in Igbo cosmology. Throughout the artwork, he simultaneously hints at spirituality and the aftermath of civil war.

Room 9 | Egonu: Painting in Darkness

Photo Credit: GGD x Tate; Will Knowledge Safeguard Freedom 2, 1985 by Uzo Egonu, oil paint on canvas, Tiana & Vikram Chellaram

The last room in the exhibition traces the life of Uzo Egonu, a Nigerian artist who built his career in postwar Britain while remaining deeply invested in questions of nationhood and belonging. After losing much of his vision in 1979 due to toxic exposure from etching, he entered what he called his period of “painting in darkness,” producing some of his most vibrant and expressive work. In Will Knowledge Safeguard Freedom 2, that tension sharpens. The title signals the pressures of nation-building, while the ladder in the painting suggests both aspiration and the weight placed on education and cultural knowledge as tools for freedom.

After Walking Through

What stayed with me wasn’t just the art. It was the viewers. White visitors from Sweden quietly repeating, “This is amazing.” A Black girl from Brazil switching between English and Portuguese on the phone, saying “wow” over and over, sounding dazed. That feeling is hard to name, but it’s real.

This exhibition reminds you that modernism was never singular or Western-owned. It unfolded in parallel, across continents, with its own theories and ambitions. The artists here were not catching up. They were building, experimenting, and thinking in real time, even if the history books did not reflect it.

There is also tension in seeing work shaped by colonial disruption and post-independence optimism gathered inside one of Britain’s most powerful cultural institutions. The contradiction is visible. Maybe that is part of the point.

More than 250 works span decades of practice once overlooked, now presented with scale and intention. An overdue correction, yes. But also a reminder that art history shifts through who shows up, who looks closely, and who finally gets to feel that awe without explanation.

Nigerian Modernism is currently on view at Tate Modern in London until May 2026.